The Gardenables – alternative for a territory in mutation(s). Lines of inquiry by Guilain Roussel (translated by David Pickering)

The territory of Aubervilliers doesn’t fit into the canonical definition of what the basis of a landscaping project should be. As a territory, it is full, really full. There is very little undeveloped area. There is no natural space to speak of and no topography: it is almost completely flat. Historically, it was Paris’ vegetable-producing region, but it was completely industrialized and developed starting in the 19th Century because of its proximity to the capital. It does not contain a major landscape set aside from the set of links represented by the canal Saint-Denis in the West and Ourcq in the East (which, being more southerly, is not in as direct contact with Aubervilliers).

Might there actually be no landscapes here? Are there places where the landscaper cannot come up with a landscape response? Can he intervene in areas other than just decorating or sprucing up projects already carried out by architects or urban planners? The landscaper, it turns out, is often only called in at the tail end of a construction project to label the plants that make up the areas of vegetation bearing the annotation “green space.”

Landscape

What IS a landscape anyway? I would say that, above all, for me, it is a unified whole that procures an emotion. A group of physical and natural elements bearing the more or less perceptible mark of human action and which has the ability to transport through its composition. That may be why the question of landscape was originally closely linked to the question of images and pictorial representation. A landscape is topography, uneven terrain, slopes, lookout points; motifs, shrubs, fields, fragmentation, patrimony, artworks; geology, the subterranean and its surface manifestations. A landscape is areas of forest and water, agricultural complexes and their open tracts of land. A landscape is all of these elements put together.

A slow but steady shift, motivated by ignorance and the preeminence of investment, sometimes overlooks a landscape’s relationship to naturally-occurring elements, trivializing spaces and paving the way for less qualitative works (under the pretext that there is no longer an original environment).

The issue of a BEAUTIFUL landscape could not be more subjective.

In the valley of Drobie, an enclosed depression in Ardèche, the hiker will find a feast for the eyes: a hidden valley couched in vegetation, rampant waterfalls, bridges of dry stones stretching like ropes between rocky, windswept mountainsides to which a few twisted pines or gnarled holm oaks hold on for dear life. But the vision of a native of the area will not be the same. Every morning, through his window, he sees a territory that has disappeared through the abandonment of agriculture. He thinks of the kilometers of stone terracing collapsing in the underbrush under the pressure of wild boars. For this person, the landscape is ugly, for it is uncared for.

In the same way, a famer in Beauce will find his perfectly-tilled fields magnificent while an individual with even the slightest awareness of the harm done by intensive farming practices will find these same fields absolutely devastated and depressing.

What interest me in this line of questioning is the notion of mental representations, of images that are conjured up by each individual’s mind. This is important when we want to think about a landscape because we are dealing with mental images that make us see reality differently.

Deep down, the purpose of a landscape design is to transform a vision of a territory or space, to give it meaning by revalorizing it, to take the time to work out structures that are sufficiently strong to gather a population around a landscape identity:

“Culture is the social space at the source of identity and meaning.

The two are inseparable. Identity and meaning give human beings

their cognitive, emotional and ethical orientation. In a word, they

are what determine and fuel all human behavior. A loss of meaning

leads to a series of destructive and aberrant behaviors. The discovery

of meaning, on the other hand, increases creativity, compassion and

productivity. At the end of the day, all power struggle is a struggle

for meaning. Why? Because human beings, deep in their nature, are

searching for meaning, even false meaning, to justify their existence.”¹

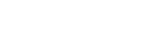

The Italian Loquat

Maria pushes open the door of her small house, revealing an inner courtyard. “This is an Italian loquat,” she tells me. She shows me the fruits and, indeed, they are not the brown loquats from the Mespilus germanica that are eaten overripe. These are round, orange, and very juicy. An amateur botanist, my first instinct when I got home was to look up the Italian loquat. I couldn’t find a thing about it. I looked for Spanish or Portuguese varieties, but fond nothing there either. It turns out that this was Eriobotrya japonica, the Japanese loquat, which is widely cultivated in warm regions including the Mediterranean Basin. When she moved to the Paris suburbs thirty years ago for her husband’s work, this sixtyish woman of Spanish origin planted a loquat tree. Alongside it grow a grape vine, a trumpet vine, and a bay laurel, as well as potted banana and olive trees. It is an integral part of her Mediterranean culture—for her, the loquat comes from Italy and represents home.

Azzedine doesn’t believe me either. The loquat can’t come from Japan, it comes from his native country of Kabylie, where it is also planted in backyards to protect the house. Tian Tian knows this fruit well, which comes from China. In Crete, Elena, on the other hand, eats the skin and doesn’t understand why anyone would peel it. I quickly realize that certain vegetables are strong common references for very different cultures.

The origin of the Italian loquat, like so many other plants, was reinvented (in Vendée, a Spanish lilac brought back by the son decades earlier turned out to be Ligustrum japonica), but the person remains convinced. In a sense, the botanical error is of little importance because it means something to the person, here and now, in the context of a globalized society. It can turn out to be a vector of communication between cultures.

Banlieue

The origin of the word banlieue [bãljø, French for suburbs], is not a “banished place” but rather an area within one lieue or league of a city, subject to a ban or law of conscription.

Might Aubervilliers, which is situated at the gates of Paris’ last city wall, les fortifs de Thiers, be more of a faubourg—a separate population center that formed outside the initial city walls under its direct influence. It is a working class area, one of the last of the “red” or communist suburbs, which have largely been stigmatized by questions of immigration.

That’s because Aubervilliers, on the margins of, and therefore cheaper than the capital, is home to immigrant workers.

Belgians, Lorrainers, Alsatians, and Bretons who arrived as early as the 19th Century were joined in the 20th by many Spaniards who came here to escape the Civil War. This produced entire ethnic neighborhoods: Little Prussia near the Quatres Chemins; and Little Spain in Landy, a neighborhood that straddles the border between Aubervilliers and Saint Denis. These populations came to work in the factories and grow vegetables.

Mainly, Aubervilliers was a vegetable-producing plain. Called la plaine des Vertus, it was situated at the southernmost border of the agricultural Plaine de France, which fed Paris. Early on, Aubervilliers counted numerous farms and related businesses. It was said that Aubervilliers produced the best vegetables of any of Paris’ suburbs. In November 1860, a farmer from the Mazier (today property of the city of Aubervilliers in preparation for a revitalization project), who worked by day and sold his wares at les Halles by night, brought an artichoke 82 centimeters in circumference and weighing three kilos to market.

That was how the yellow Paille des Vertus onion became the plain’s specialty and the Milano Cabbage came to be known here as the Aubervilliers Quick Cabbage. In other words, these were new local plants with recomposed identities.

Industry quickly got hold of this turf with hospitable topography and a large working-class community within close proximity of Paris. Among many others, the Lourdlet Cardboard Factory, the La Nationale Cannery, a match factory, the Sain Gobain Glassworks, Edmon Jean Ceramics, and the LT Piver Perfumery, deeply marked the architectural and social identity of the city. Italians, Portuguese, Africans, North Africans and Asians joined the Aubervilliers landscape, which more than seventy nationalities now call home. In the 1970s, much construction took place in the interstitial zones between Aubervilliers, Saint-Denis and La Courneuve. Shantytowns and slums were razed and haphazardly replaced with large housing projects. Initially meant to be temporary, many are still standing.

What interests me as a landscape artist is the fact that Aubervilliers is one of those places in the shadow of the city, the capital, and of society. It is a space that has not lost the richness, diversity and potential of the social margins.

Paris is no longer a place where a new way of experiencing the city will be invented: cultural centers that haven’t been turned into supermarkets are almost all institutionalized or conventional. The last great industrial wastelands are being turned into public parks or have been slated for housing or office developments.

The city is overflowing; we are even starting to cover the peripheral boulevards in order to find space and launching all the plans imaginable to pack even more in.

Still, the city needs a margin if it isn’t to freeze up, if it is to remain creative, rich and diversified.

For Paris, the game is up. It would take a great shake-up, a catastrophe or, god forbid, a war, to start to imagine the use of the city, the relationship to patrimony and urban structure differently.

Urban Projects

Let’s design a great project. Let’s find investors to build. Out with the old and in with the new. Everything goes. Everything is a little old and dirty anyway.

Observe the territory. Look at the projects in the works.

The La Plaine, Stade de France neighborhood is at the center of service sector investment in the region.

But one soon realizes that the projects underway there are paradoxically intended for other places.

The sad rush-hour dash of people in blouses and suits swarming into the RER station on their way to glass office buildings. They retrace their steps in the evening, going back toward other suburbs. These are neighborhoods that alternate, dying brutally every day.

Hours spent in public transportation. A tunnel that encourages us to ignore our surroundings so that we can live further away and get home faster.

Vacation in Seychelles to unwind, to consume landscapes without worrying about the environmental impact. If one is to enjoy ones stay—and return to work at the Plaine Saint-Denis in top form—it is best not to think about the garbage produced by the tourism industry.

Position

What the landscape artist can contribute is that his work is based on a SITE. That means he must try to reveal a territory’s hidden resources and to question the location’s identity.

I would like to promote the human and botanical strength of this territory. I think that working on a site means working on the HERE and NOW. The sustainable city must not become spatially and architecturally uniform to the detriment of diversity in all its forms.

Why not see the city as a sensitive surface made to accommodate life?

Building complexes are abiotic factors of this highly complex urban ecosystem. They are made of rock, inert material with, by its very nature, a direct influence on its environment (temperatures, conditions of life, etc.). Life may or may not be able to take root in these constructions depending on the texture of their materials, what material from the sky it can retain, from the smallest to the greatest scale. From the macro to the micro.

Texture and Life

The butterfly bush, which emigrated from Asia and is planted in gardens, escaped. It turns out it is actually quite nomadic and wanders into forgotten places. It colonizes the suburbs.

Its seeds fly easily, the wind carries them and they lands on rough surfaces.

There is no earth, there is nothing. The butterfly bush, this intruder that “destroys natural habitats,” has settled here and takes the first steps toward a new form of life. It creates an environment, even a microscopic one, where there wasn’t one before.

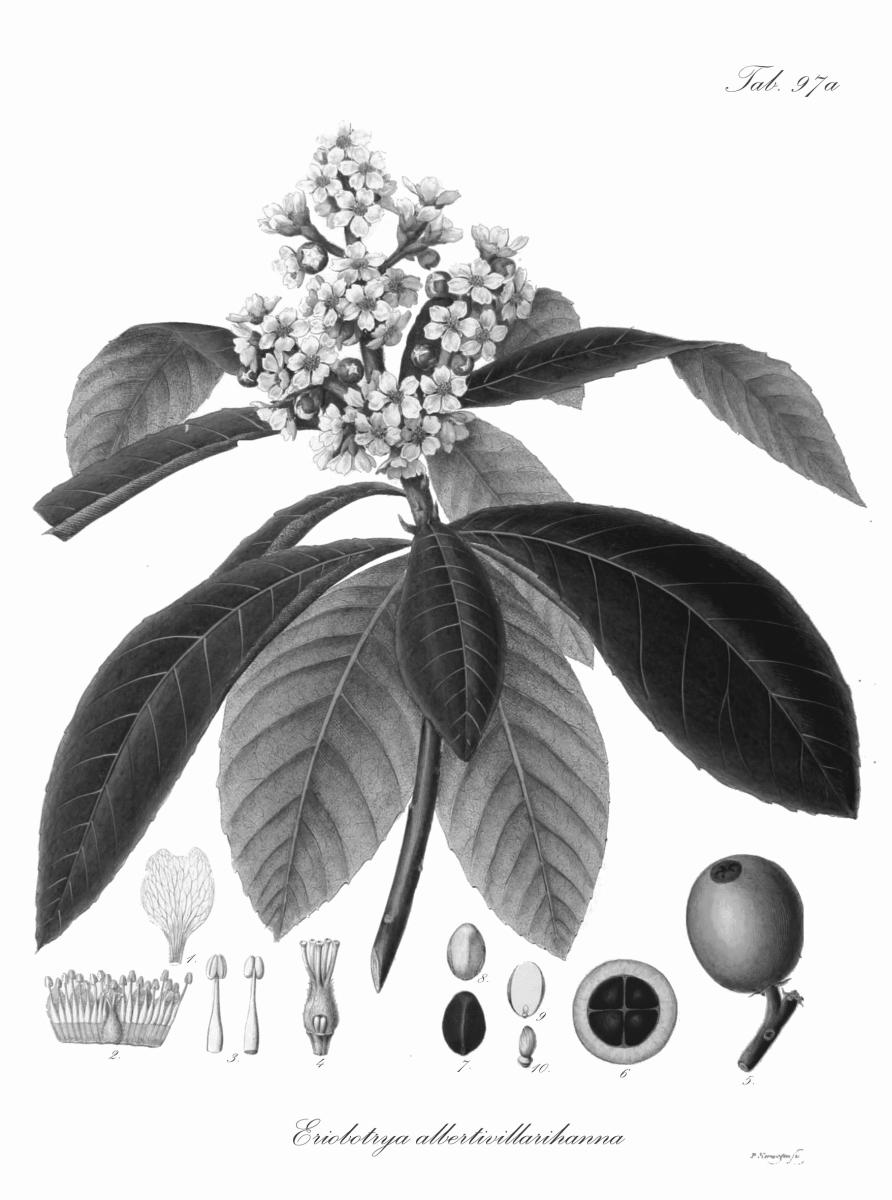

What makes the city’s texture? A group of bumps added together.

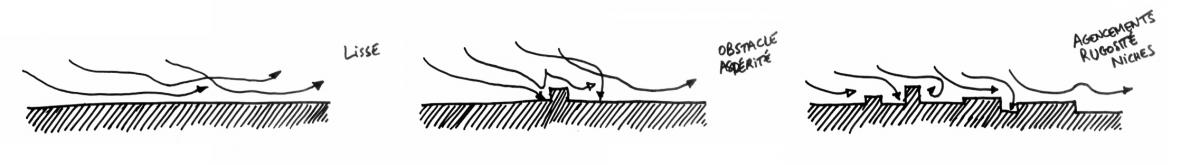

The air hauls a great quantity of particles, grains, pollen, and dust, which are constantly being dumped onto the surface of the earth. These elements are churned in the wind and local factors encourage them to take root, or don’t. As soon as there is an obstacle, a snag, an accumulation can occur.

Accumulations occur depending on the assembling of these snags and feed off themselves. The accumulation leads to accumulation, and so on and so forth.

The equation is therefore organized by the air pressure on whatever material nature decides. Just as the sum result of human factors on a landscape is the result of the pressure of the environment (air, man, animals) on abiotic factors (primary or secondary).

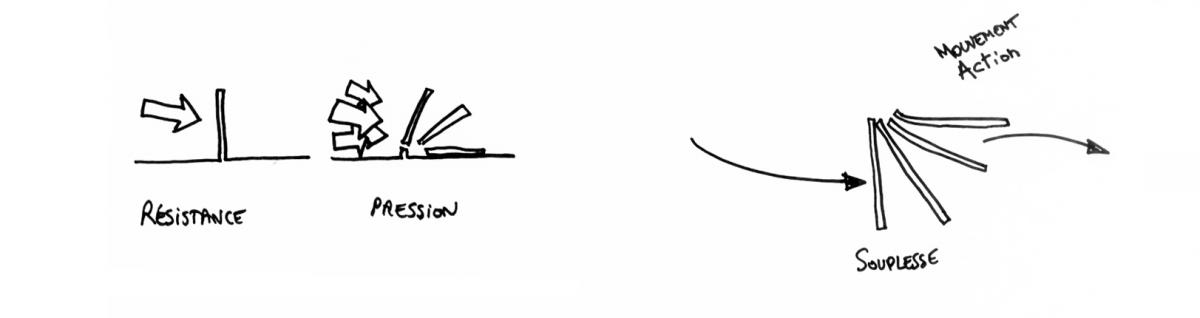

The material’s resistance enters into play. Its construction allows it to stand the pressure. If the pressure increases, a point is reached when the material can no longer resist. It breaks.

The material can bend. It can even move if it is part of a system that allows this. In this case, the pressure acting on a material has a positive effect and transforms the constraint into energy.

Through the extreme use of this territory by man, the entire ecosystem is forced into re-composition and reinvention. In the recesses, the vacuums of activity, materials have accumulated. Progressively life has taken root. A flora now composes the new urban ecosystems.

Should we condemn so-called invasive spaces that colonize places where there is sometimes not even soil, water, and where nothing grows? All the butterfly bush seed needs to bud is a snag.

Thinking of the city as a receptive surface that latches onto life means imagining a diverse and rich city. It means considering the presence of varied “natural” spaces in urban planning as primordial and worthy of being prioritized in economic development projects. It may be the first step toward inventing a more sustainable city that can be projected 20, 50 or 100 years into the future, with marginal spaces, spaces for play, spaces that provide a breath of fresh air and escape. These possible lines of inquiry orient my approach to landscaping in the territory of Aubervilliers, where I have settled.

Text published in Le Journal des Laboratoires September-December 2011

-----------------------------------

Author's notes: The program at the Ecole nationale supérieur du paysage de Versailles, in which I was enrolled between 2006 and 2010, confers the degree of landscaper DPLG (government certified), and is centered around project workshops based on actual sites and is supervised by landscaping professionals. The program’s senior year ends with a thesis project in which the student chooses a study site and defends an approach. He is supervised by a professor who feels an affinity to his approach and accompanies him in his project.

Gilles Clément agreed to supervise my work on Aubervilliers. I chose the subject because, after several years spent mounting the theater project downtown with my association (Les Frères Poussière) without ever imagining that it was a territory that could be the subject of a landscape project of great scale. The personal motivation to undertake a landscaping project on the Aubervilliers territory didn’t come out of a first impression, as it can on certain sites one visits.

¹ Cf. Perlas, Nicanor. La société civile, le 3° pouvoir, Barret-le-Bas (Yves Michel, 2003, p. 201)